News > Immigration In Minnesota

“I believed that opportunity would open:” After his refugee journey, Laueh Roland opens opportunities for others

Posted on Jun 29 2020

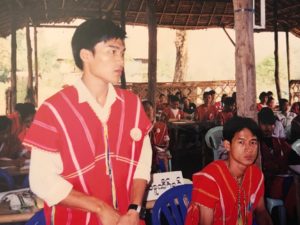

Congratulations to Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota (ILCM) legal assistant Laueh Roland, who recently received the MSBA’s 2020 Bernard P. Becker “Advocate” Award for outstanding legal service to low-income clients. Laueh came to the United States from a Thai refugee camp in 2008, earned a paralegal degree at Inver Hills Community College in 2017, and has served in ILCM’s refugee program since 2011. The Becker Award is a milestone for Laueh on a long journey that began in Burma when he was only thirteen years old.

“I gave up my home for an education,” Laueh says about his 2008 trip from Thailand to the United States. He was about 23 years old then, and it was the second time he had made that sacrifice. The Thai refugee camp had been a good place to live, he says—better than the mountain forests of southeastern Burma (now called Myanmar), which he and his Karen family had fled 10 years earlier. The Karen people had occupied that rugged landscape for centuries, one of several ethnic groups in the area. For Laueh’s family, the problem with Burma’s forests was not the steaming tropical heat or even the swarms of mosquitos. Those were familiar hardships in the area: the real problem was the Burmese army.

Before entering Thailand, Laueh and his family had lived in a part of Burma where civil war had continued intermittently since independence in the late 1940s. A succession of military governments ruled the country, and had long been terrorizing groups who opposed them. In 1989, the military government changed the name of the country from Burma to Myanmar. At the time that Laueh’s family lived there, their home was in contested Burmese territory controlled by Karen rebels. While the two armies fought, Laueh’s family tried to farm.

Neither life nor farming went well. The problem with farming was that Burmese troops would launch random attacks on any Karen civilians living in contested territory. Friends sometimes gave advance notice of raids, but you never really knew when soldiers would show up to harass people, burn property, and destroy food stocks and crops. The rebel army provided security when it could, but the Burmese troops were persistent and vicious. That meant that when an alarm was given, people in the forest and fields had to hurry home to gather up a few belongings and then dash into the jungle. The attacks forced Laueh and his family to move many times, sometimes leaving behind a dwelling, personal property, or crops in the fields. The people never quite knew what violence to expect, or when it would happen again—or how they would live while reestablishing themselves in another area.

“You couldn’t live like that,” Laueh says “There was no security, no way to farm the jungle in that area. There was no way to educate kids.” After years of abuse from the Burmese army, Laueh’s parents and their three children left their home and fields and traveled on foot to refugee camps in Burma close along the Thai border. Laueh was about 13 years old; his siblings were younger. The journey through the jungle took more than two weeks. The Burmese government permitted this because it wanted the Karen people out of Burma.

By 1997, over 100,000 Karen and other peoples had already fled southeast across the border into Thailand. The Thai government, with help from the United Nations and other organizations, had established nine refugee camps in the rugged jungle country just inside the Thai border. After some time along the border in Burma, Laueh’s parents and their three children were allowed to cross into Thailand—another long journey on foot—and finally to settle in one of the Thai camps. After that, life got better for them, at least in some ways.

“Life was more civilized in the camp”

“There was more protection,” Laueh says, “and more chances in life.” In parts of Burma controlled by rebels, Karen schools had been closed because of frequent Burmese army attacks. In contrast, the camp offered education for children and vocational training for adults, including instruction about how to live in the camp “cities,” which was different than farming in the jungle.

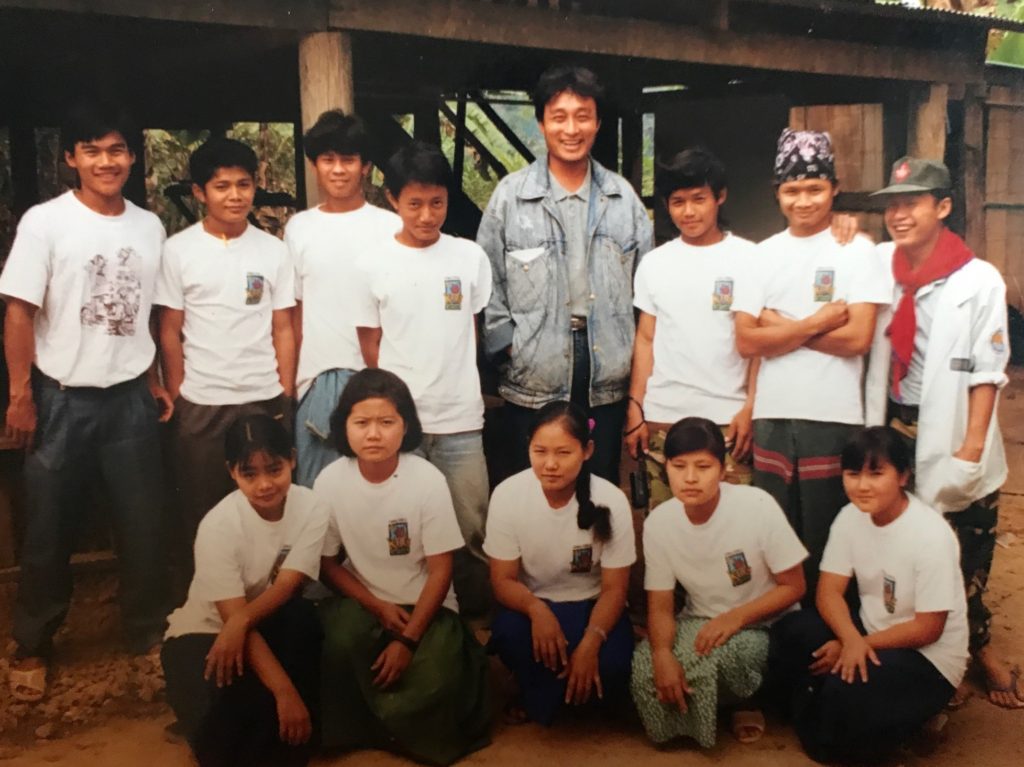

Refugees were not allowed to venture outside the camps, but with help from the Thai government, the United Nations, and other global organizations, people in the camp received basic food and health care. “Life was more civilized,” Laueh says. He and other teenagers received vocational training and lessons in advanced English. There were courses in refugee issues and instruction about international communities. People were introduced to the bureaucratic processes by which they might someday be allowed to settle permanently somewhere else.

Not all Karen teens were enthusiastic about those classes. “You know how teenagers are,” Laueh says, “Kids might be interested or not.” It was easy for some to get derailed in camp, but those who thought of the future were interested. Laueh believed he should “pay attention and get education. I prepared for my future. I believed that opportunity would open,” and he wanted to be ready.

Two years passed while Laueh was preparing and nothing much had changed. He was beginning to feel “hopeless,” he says, until he heard on the radio that the United Nations would be creating a resettlement program to aid Karen refugees. International organizations were already planning to work in Burma and Thailand. “It was like the answer to my prayers,” he said; now he felt “excited about preparing for when the time would come to me.”

In camp classes, he had learned about international human rights and American constitutional law. He was interested in law and, after the chaos in Burma, he associated it with civilization. He was looking forward to further education, to a “sustaining job,” and a nice house. He hoped “to be happy and start a new life.”

Laueh saw the chance for education and opportunity elsewhere and, when finally offered the opportunity, left the Thai camp for the United States. After ten years in Thailand, however, Laueh’s parents had grown to like the secure life in camp with people they knew. They were especially apprehensive about going to a faraway place where they did not speak the language. Ultimately, they chose to stay in Thailand. His father passed away there, and later, after the situation in Burma had improved, his mother and siblings returned to their home country.

“You must change your life; you must change everything.”

The resettlement process took almost two years: applications, screenings, interviews, presenting documents. “You had to prove everything and then wait,” Laueh says.

The United Nations, NGOs, foundations, and religious organizations kept things moving by providing sponsorship, orientation, vocational training, and basic financial aid. Still, Laueh’s first year in Minnesota was “tentative and difficult. There was snow. I did not know what to do, where to go, how to drive. I felt like I was not able to survive in that first month or year.” Despite all the help refugee organizations provide, Laueh says, many new refugees become depressed during resettlement. “I had to manage my depression, overcome it—negotiate with the situation and adapt.”

Part of that process was finding a “sustaining” job. “When I came to the United States, I would have taken whatever job I could, because it would be my opportunity, but I didn’t expect this kind of job,” he says about ILCM. He was still interested in education and the link between law and civilization when he learned that the large Karen community in Minnesota needed a legal worker to speak for them. “Then I heard that ILCM was looking for a staff member who could speak my own language. I think it was just the right time, the right place, the right language.” The time had come to him.

“It felt like a big achievement.”

Laueh is grateful that the position included training opportunities and encouragement to complete a paralegal program at Inver Hills Community college. Feeling well-supported by his colleagues, he enrolled in other training through ILCM and took on work tasks that led to his accreditation by the Board of Immigration Appeals. This credential allows appropriately trained people without a law degree to provide legal advice or represent immigrants in some legal processes. Laueh’s work has focused on helping Karen refugees in Minnesota adapt and become U.S. citizens.

Laueh’s work with the local Karen community showed him how important it is for recent refugees to understand the law where they live. Life in Burma could be both authoritarian and chaotic. “Some refugees do not understand democracy and freedom. They think liberty means they can do whatever they want,” he says. “Karen people here need to know immigration laws and apply them every day in their own lives. They need to know that even if they have a green card, they could be deported if they do not obey the law. They need to know about rights and responsibilities.”

Asked what he likes about his ILCM job, Laueh remembers his work with long-displaced refugees. Some of them were 50 or 60 years old, he says, “and never ever in their entire lives had they been recognized by any government as a legal citizen, and never had they participated in a democratic process like voting. It felt like a big achievement for me to help them become government-recognized citizens and voters.”

Laueh says his most memorable case involved a family who had come to the United States over 20 years ago as children, while their parents had stayed behind. Once here, the children could not go back to Burma to visit the mother. When Laueh learned about them, they had finally become citizens and now wanted to bring their parents here to join them. Laueh worked on the family reunification case until it ended happily: “Right now they are reunited in St. Paul. They are together, so the mother can see the children and the children can take care of the mother, so this is a very, very, very memorable case.”

The U.N. High Commission on Refugees reports that 93,000 Karen refugees currently live in Thai camps. Many have relatives already resettled in the United States, but family reunification has become more difficult in recent years due to U.S. travel bans and shrinking refugee quotas, and to the U.S. government’s decision several years ago to end the special resettlement program under which Laueh arrived.

Laueh considers Minnesota a good place for Karen refugees to resettle, because there is already a community of about 17,000 Karen, mostly in the Twin Cities and southern Minnesota. He says new refugees will be less isolated where they can speak their own language, create relationships, visit with family, and join church activities. Also, refugees can find English-language help here, as well as businesses that need immigrant workers, and accessible social services. In 2016, the monthly income for an “average Karen family” in Minnesota was reported in MINNPOST as “$1000-$2000, or less.”

Laueh hopes to see more Karen refugees become successful Americans, like other immigrant groups in the past. He already sees Karen young people graduating from high school and going on to college. In the future, he expects more younger Karen to become “nurses, doctors, educators, lawyers, military service members, pastors, and other community leaders.” For his own young children, Laueh says he wants to “pay attention now and prepare for their future education, get them to go in the right direction to become professionals. Therefore I have to set a good example and show them, ‘See, you can learn from me.’” In the future, he wants to say to them, “Look at me. I went to high school in a Burma camp. Even though I don’t have a higher education like you, I have given you a college education, so now you must surpass me.”

——-