How Immigration Became So Controversial

Does the hot-button issue of 2018 really split the country? Or just the Republican Party?

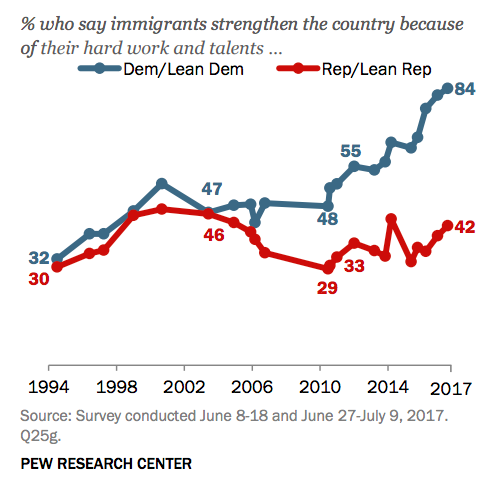

Immigration seems to be the most prominent wedge issue in America. Senate Republicans and Democrats shut down the federal government over the treatment of immigrants brought to the U.S. illegally as children, also known as Dreamers. In his State of the Union address on Tuesday, President Donald Trump referred to U.S. immigration law as a “broken” system; one party clapped, the other scowled. This polarized reaction reflects a widening divide among voters, as Democrats are now twice as likely as Republicans to say immigrants strengthen the country.

These stories and others might make it seem like most Americans are anxious about the deleterious effects of immigration on America’s economy and culture. But along several dimensions, immigration has never been more popular in the history of public polling:

-

The share of Americans calling for lower levels of immigration has fallen from a high of 65 percent in the mid-1990s to just 35 percent, near its record low.

-

A 2017 Gallup poll found that fears that immigrants bring crime, take jobs from native-born families, or damage the budget and overall economy are all at all-time lows.

-

In the same poll, the percentage of Americans saying immigrants “mostly help” the economy reached its highest point since Gallup began asking the question in 1993.

-

A Pew Research poll asking if immigrants “strengthen [the] country with their hard work and talents” similarly found affirmative responses at an all-time high.

But immigration is not a monolithic issue; there is no one immigration question. There are more like three: How should the United States treat illegal immigrants, especially those brought to the country as children? Should overall immigration levels be reduced, increased, or neither? And how should the U.S. prioritize the various groups—refugees, family members, economic migrants, and skilled workers among them—seeking entry to the country? It’s possible that most voters don’t disentangle the issues this specifically, and don’t think too much about the answers to each question. After all, immigration ranks quite low on Americans’ policy priorities—it’s behind the deficit and tied with the influence of lobbyists—which makes responses shift along with the positions of presidential candidates, political rhetoric, or polling language. (You might, for example, get very different answers to questions emphasizing “law and order” versus the general value of “diversity.”)

On the most important immigration question—the “levels” question—it doesn’t seem quite right to say the issue of immigration divides America. It more clearly divides Republicans—both from the rest of the country, and from one another. Immigration isolates a nativist faction of the right in a country that is, overall, growing more tolerant of diversity. January’s government shutdown is a perfect example. Nearly 90 percent of Americans favor legal protections for Dreamers, but the GOP’s refusal to extend those protections outside of a larger deal led to the shutdown of the federal government, anyway.

What’s more, immigration pits Republicans against Republicans. On one side are the hard-line restrictionists, like White House aide Stephen Miller and—depending on the time and day—Donald Trump. This group favors a wall, rising arrests and deportations for undocumented workers, and a permanent cut in the number of immigrants that can enter the U.S., particularly (if you heed the president’s scatological commentary) from Latino or majority-black countries. Nativism runs deep among Trump’s most ardent supporters. Three-quarters of them say “building the wall” should be the highest priority of his presidency, while a majority of Americans say it shouldn’t be a priority at all.

But there is another side of the party, epitomized by its reliably pro-immigration donor class. In 2016, the Chamber of Commerce, a bastion of Reaganite conservatism, released a report concluding that immigrants “significantly benefit the U.S. economy by creating new jobs and complementing the skills of the U.S. native workforce.” The Koch Brothers and their influential political group Americans For Prosperity loudly decried Trump’s immigration plans back in 2015. It wasn’t so long ago that this wing seemed to be the future of the party. The GOP’s “post-mortem” report on the 2012 election stated plainly, “We must embrace and champion comprehensive immigration reform,” and the presidential candidates with the most donor support in the 2016 election were Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio, both of whom have supported high levels of immigration with something like amnesty for undocumented workers.

This tension within the Republican Party could be summarized as “ICE versus Inc.” In early January, federal agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, raided nearly 100 7-Eleven stores across the country and made almost two dozen arrests. Along with the wall, these agent arrests, up more than 40 percent under Trump, are the clearest manifestation of the administration’s crackdown on illegal immigration. But the Koch brothers, motivated by an interest in expanding the GOP coalition and providing corporations with cheap labor, have funded initiatives to attract Latino votes by helping undocumented workers with tax preparation, driver’s tests, and doctor’s visits. The modern GOP is an awkward political arrangement, in which pro-immigration corporate libertarians are subsidizing a virulent anti-immigrant movement.

The immigration issue was never easy. But it hasn’t always been this confusing.

For much of the 1990s, the two parties were essentially in lockstep on the issue of immigration. In 2005, Democratic and Republican voters were 5 percentage points apart in their favorability toward immigrants, according to Pew Research Center. But in the last 13 years, attitudes toward immigrants have forked dramatically between the two parties. Today, eight in 10 Democrats and Democratic-leaning voters say immigrants strengthen the country, twice the share of Republicans.

What happened in the mid-2000s to cleave the bipartisan consensus? In 2006, President George W. Bush pushed a comprehensive immigration-reform bill that failed in Congress. While the Senate draft created a path to legalize unauthorized immigrants, the House legislation emphasized border security and punishment for undocumented workers and their employers. The latter bill inspired a round of pro-naturalization protests across the country, which, in turn, caused a backlash among conservative voters. By the end of this maelstrom of bills and backlashes, comprehensive reform had failed and the parties had sharply split on the immigration issue. The latter is evident in the polling, which shows 2006 as the year when Democrats and Republicans split dramatically.

This split intensified under Obama, the 2016 presidential campaign, and Donald Trump’s presidency. After the Great Recession, white men without a college degree sharply soured on America’s future, and in polls conducted by Kellyanne Conway’s firm in 2014, many explicitly blamed illegal immigration for their economic plight, despite uneven evidence. Donald Trump harnessed this resentment of less educated whites from the start, using his first speech as a presidential candidate to accuse illegal immigrants of importing crime, drugs, and sexual assault.

But the above graph shows, it’s also the case that the Democratic Party has become much more accepting of immigrants—some might say even radically accepting, compared with recent history. There are several possible reasons. As the Hispanic population grew in the 2000s, labor unions that once feared the effect of cheap labor on their bargaining power came to see the naturalization of undocumented workers as a necessary step forward for labor relations. Meanwhile, as Hispanics became the fastest-growing ethnicity within the Democratic Party, Hispanic leaders lobbied for more pro-immigrant policies. Finally, as The Atlantic’s Peter Beinart has written, left-leaning tech leaders have pushed for expanding H-1B visas to let more high-skilled immigrants into the economy.

It’s possible that Democratic unity on immigration is just a proxy for unified opposition to Trump and that, in power, the party would face similar internecine fights over how to legislate on immigration. But this would be unfortunate, because the case for high levels of immigration remains quite strong.

The most common economic arguments against immigrants, particularly those that are low-skilled workers, are two-fold. First, there is the concern that new arrivals pull down wages for the low-income Americans with whom they compete. The evidence here is mixed and controversial, but a 2008 meta-analysis of more than 100 papers studying the effect of immigration on native-born wage growth characterized the impact on wages as “very small” and “more than half of the time statistically insignificant.” Second, there is a concern that immigrants are a drain on federal resources. It’s true that the first generation of low-skilled adults can receive more in health care, income support, and retirement benefits than they pay in taxes. But as their children grow up, find jobs, and pay taxes themselves, most immigrant families wind up being net contributors to the government over their decades-long residence in the U.S., according to a 2016 report from the National Academy of Sciences.

Too often lost in this discussion of wage and budget effect is the question of whether a rich country has a moral obligation to help poor families—particularly those in political distress—by admitting them as legal immigrants. The single most unambiguous, most uncontroversial fact about immigration is that it raises the living standards of poorer foreign-born workers. It is, essentially, the world’s most effective foreign-aid program on a per capita basis. But, more than mere charity, high levels of immigration seem to materially benefit the United States. America’s immigrant population is in many ways a model of the future of the country—more entrepreneurial, more likely to move toward opportunity, and all together more dynamic. To regard this community as something the United States should banish from the body politic is to mistake a vital organ for a cancer.

I have written that the current demographic and political makeup of the U.S. electorate (and other countries) makes it vulnerable to a race-baiting populist like Donald Trump, who can marshal the latent tribalism of a fading white majority to harass immigrants. But the United States’ demographic picture is changing quickly. The generation of Americans under 30 are the most diverse cohort in the U.S., the most fervently against the construction of any wall, and the most accepting of immigrants, even those that don’t speak fluent English.

The majority of children born in 2015 were non-white. That means even if the GOP hardliners managed to permanently end immigration this weekend, the United States’ white majority would decline into one of many non-majority pluralities within a few decades, anyway. No matter whether the future of the Republican Party is Stephen Miller or the Koch Brothers, multiracial nationalism is the future of the United States. No other nation is on the way. There is no other future to unite around.