“On Real ID, Democrats already have done their part: they’ve compromised. Democratic Gov. Mark Dayton has, too.

“That means it’s Daudt’s turn.”

“On Real ID, Democrats already have done their part: they’ve compromised. Democratic Gov. Mark Dayton has, too.

“That means it’s Daudt’s turn.”

The U.S. government will not extend Temporary Protected Status for citizens of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. The TPS status granted because of the past Ebola outbreak will terminate on May 21. That means thousands of people from Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone must leave the United States unless they have acquired a different immigration status.

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) allows people from certain countries to remain in the United States and to get temporary work permits due to an emergency situation in their home countries. The Secretary of Homeland Security issues the TPS determination, and can renew or terminate the status. As John Keller, executive director of the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota, explained in a 2016 MinnPost interview:

“Well, think of TPS as this magic protection that happens because of circumstances that occur in your home country. If you happen to be outside of your country and in the U.S. when a massive earthquake hits, like in Haiti, the U.S. is saying, it would be inhumane to send Haitians back to a country that has been destroyed. So, any Haitians in the U.S. on the date of the hurricane, will now be protected.”

Currently, TPS applies to 13 countries. That status will end for Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone on May 21.

Haitian TPS will end on July 22. Haitian TPS was granted after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, which has still not rebuilt and recovered from the earthquake.

Haiti was also hit by Hurricane Matthew last October, and by a cholera epidemic attributed to UN peacekeepers that began in 2010. The cholera epidemic has killed nearly 10,000 people and infected more than 770,000 Haitians.

However, on April 20, an internal memorandum signaled that the Trump administration may refuse to renew Haitian TPS. According to Al Jazeera:

“]T]he acting director of US Citizen and Immigration Services (USCIS), a Department of Homeland Security agency, recommended that the status not be renewed in an internal letter, USA Today reported last week.

“In the letter, James McCament, the USCIS acting director, concluded that while Haiti has not completely recovered from the earthquake, it was stable enough to end the status, the news organisation reported.

“John Kelly, the Homeland Security secretary, will make the final determination. He had not made a decision as of April 21, a spokesperson told Al Jazeera English.”

Time is running out for TPS holders from Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone. On April 28, an ILCM Facebook post urged them to seek help immediately:

“Dear friends from Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone in MN who currently have (or know someone with) TPS based on the Ebola-based protections. USCIS announced in the fall of 2016 that TPS would end on May 20, 2017. This notice confirms that it will in fact end in three weeks. If you had a status prior to TPS – you may be able to return to that status. If you did not – you are expected to depart from the U.S. We encourage everyone to consult with an experienced immigration attorney ASAP to determine if there is any other possible protections for you. DO NOT DELAY. If you are low-income please call ILCM at 1-800-223-1368 or 651-641-1011 for more information. You can also find immigration attorneys in MN and nationwide at www.aila.org“

From 2010-2014, the biggest numbers of new Minnesota immigrants came from three countries: India (2,000 annual arrivals), Mexico (1,600 arrivals), and China (1,500 arrivals). A total of about 24,000 immigrants from other countries arrived each year.[1]

But that’s just the newest arrivals. Overall, immigrants from Mexico make up the biggest group of foreign-born Minnesotans – some 67,000, according to the 2015 American Community Survey figures.[2] Are Hmong Minnesotans the next biggest group? Not according to the official figures, which don’t count Hmong as a single group, but rather use nationality, which divides the Hmong Minnesotans between Laos and Thailand.

Immigrants make up 13.5 percent of the national population but only 8.3 percent of Minnesota’s population in 2015. The “Getting to know new Minnesotans” series explores some of Minnesota’s immigration picture. Click here for Part One: How many immigrants?

Here’s how the Minnesota State Demographic Center sums it up:

In 2014, the largest groups of foreign-born Minnesotans were born in Mexico (about 66,000); India (29,000); Laos, including Hmong (28,000); Somalia (26,000); Ethiopia (18,000); China, excluding Hong Kong and Taiwan (18,000); Thailand, including Hmong (17,000); and Vietnam (17,000). These estimates do not include U.S.-born children of these immigrants. They also likely underestimate the size of our immigrant populations because trust and language issues reduce response rates to Census surveys.[3]

Where are the Somali Minnesotans in this count? The U.S. Census figures don’t show Somalis at all in 2014, counting them in with “other East African” countries.[4] In 2015, the census figures show Somalis separately, reporting about 84,000 in the entire United States, with 25,000 of that number in Minnesota.[5] As noted in the state demographer’s report, the reported number is likely lower than the actual number.

Sometimes people get confused about who immigrants are. For example, many people think all people of Latino ancestry are immigrants. That’s not accurate. In Minnesota 105,000 people of Latino origin are foreign-born, but 177,000 are U.S.-born. Most Latinos in Minnesota were born in this country so they are not immigrants.[6] Even among those who were born outside the country, many are now U.S. citizens.

Not all Latino or Hispanic immigrants come from Mexico. Some 46,000 immigrants in Minnesota come from other Latin American countries. Guatemala, El Salvador, and Ecuador lead the way, with between five and six thousand immigrant Minnesotans from each country. About 3,000 Minnesota immigrants come from Colombia and another 3,000 from Honduras.

Many other countries have large immigrant populations in Minnesota. Those with more than 5,000 immigrants, according to 2015 American Community Survey data, are:[7]

[1] Minnesota on the Move: Migration Patterns and Implications, Minnesota State Demographic Center, January 2015, p. 11 <https://mn.gov/admin/assets/mn-on-the-move-migration-report-msdc-jan2015_tcm36-219517.pdf>

[2] U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates <https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk >

[3] Minnesota State Demographic Center, Immigration & Language, consulted 4/25/17. < https://mn.gov/admin/demography/data-by-topic/immigration-language/>

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates <https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk >

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates <https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk >

[6] State Immigration Profiles – Minnesota. Migration Policy Institute. Consulted 4/25/17. <http://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/state-profiles/state/demographics/MN>

[7] U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates <https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk >

“Across the Americas, immigrant communities are under attack.” That’s why Hispanics in Philanthropy launched its new campaign, #LATINXSBELONG BECAUSE #WEALLBELONG on May 1. The Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota (ILCM) is part of the campaign, with #LatinxStrong, an appeal to raise $30,000 to support its work of representing immigrant families, advocating for just immigration policies, and educating immigrants and the larger community.

Hispanics in Philanthropy says, “the increasing need is stretching critical resources thinner than ever” for nonprofits working with immigrant communities, and that, “From defending their legal status to providing direct services, these nonprofits fill critical gaps.”

In immigration cases, unlike criminal cases, immigrants do not have a right to a public defender. That’s why ILCM legal services to immigrants are so important. According to the American Immigration Council:

“Whereas in the criminal justice system, all defendants facing even one day in jail are provided an attorney if they cannot afford one, immigrants facing deportation generally do not have that opportunity. …Yet, in every immigration case, the government is represented by a trained attorney who can argue for deportation, regardless of whether the immigrant is represented….

“The data show that immigrants with legal counsel were more likely to be released from detention, avoid being removed in absentia, and seek and obtain immigration relief.”

Representation in immigration cases is crucial, and ILCM works every day to represent immigrants with legal matters from from fighting deportation to becoming a naturalized citizen. On its #LatinxStrong page, ILCM writes:

“All of our offices have a waitlist for services, and, especially in this dangerous climate, where ICE arrests have increased by 80 percent in and around Minnesota, we need more legal staff to meet the increasing needs – for representation, for advocacy, and for education.”

As the campaign launched on May 1, ILCM was the only Midwestern project seeking support through #LATINXSBELONG and Hispanics in Philanthropy.

In a 49-page decision on April 25, U.S. District Judge William Orrick III issued a preliminary injunction against enforcement of President Donald Trump’s executive order penalizing sanctuary jurisdictions – section 9(a) of the executive order. The order came in a case brought by the city and county of San Francisco challenging Trump’s executive order and its enforcement by federal agencies. The injunction means there can be no action against sanctuary cities under the executive order while the case proceeds to a full hearing.

Judge Orrick said it was clear that the executive order meant to withhold federal funds for more than law enforcement:

“The rest of the Order is broader still, addressing all federal funding. And if there was doubt about the scope of the Order, the President and Attorney General have erased it with their public comments. The President has called it ‘a weapon’ to use against jurisdictions that disagree with his preferred policies of immigration enforcement, and his press secretary has reiterated that the President intends to ensure that ‘counties and other institutions that remain sanctuary cites don’t get federal government funding in compliance with the executive order.’”

The preliminary injunction applies not only in San Francisco, but nationwide. The injunction “does not impact the Government’s ability to use lawful means to enforce existing conditions of federal grants or 8 U.S.C. 1373, nor does it restrict the Secretary from developing regulations or preparing guidance on designating a jurisdiction as a ‘sanctuary jurisdiction.’”

White House chief of staff Reince Priebus called the ruling “the 9th Circuit going bananas” and said the administration will appeal.

President Donald Trump told the Washington Examiner that he “absolutely” has considered breaking up the Ninth Circuit – the federal circuit that includes California, Hawaii, and seven other western states. He called the Ninth Circuit “outrageous.”

Can the president break up the Ninth Circuit? Not really – any reorganization of federal district and appellate courts would have to go through Congress. That would take a long time, and it’s difficult to see how it would make any difference in the court decisions ruling various parts of Trump’s executive orders unconstitutional.

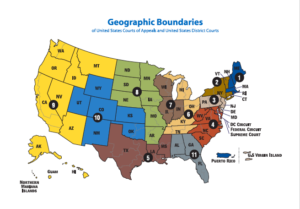

The federal court system starts with trial courts – the 94 district courts. The latest ruling came from a federal district court in San Francisco. An appeal – if there is one – would go to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. So far, the sanctuary case has not reached the Ninth Circuit.

The Ninth Circuit is one of the 13 federal appellate courts, which hear appeals from district court decisions. Twelve of the circuits are based on geographic area, with the Ninth Circuit including California, Hawaii, Alaska and six other western states. The Appeals from Ninth Circuit (or any other federal appellate court) decisions go to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Thirteenth Circuit, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, hears patent law appeals, some administrative matters, and other subject matters set by Congress.

“Immigrant advocates highlighted the increased percentage of immigrants without criminal convictions: about a quarter of those arrested locally, compared with 10 percent in 2016. That increase reflects a return to a more traditional enforcement approach, ICE said.”

Warning! According to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), scammers are trying to steal personal information by pretending to be immigration officials. [Para Español, haga clic aquí.] According to the DHS alert, the scammers make it seem that they are calling from an official DHS telephone number. That is called spoofing – hiding the caller’s real telephone number and making it look like they are calling from a different number. This is a way that criminals try to steal from people, and try to get personal information and commit identity theft.

The scammers calling from the DHS number pretend to be U.S. immigration employees. They demand to obtain or verify personally identifiable information. Sometimes they even say that the person they are calling is a victim of identity theft, and that they are trying to help.

If someone calls you and asks for personal information or payment, HANG UP THE PHONE.

The real DHS Hotline is used only to give out information and answer questions, never to ask you for information.

The U.S. Citizenship and Information Service (USCIS) says that anyone who wants information about their immigration case or status, can find that information in three ways:

The Department of Homeland Security also wants people to help in tracking the criminals who are pretending to be immigration officials. They say:

“Anyone who believes they may have been a victim of this telephone spoofing scam is urged to call our Hotline or file a complaint online via the DHS OIG website www.oig.dhs.gov. You may also contact the Federal Trade Commission to file a complaint and/or report identity theft.”

The number of the DHS/OIG hotline is 1-800-323-8603.

¡CUIDADO! Según el Department of Homeland Security (DHS), los estafadores están tratando de robar información personal, fingiendo ser funcionarios de inmigración. [For English, click here.] Según la alerta de DHS, los estafadores simulan que están llamando desde un número de teléfono oficial de DHS. Eso se llama “spoofing” – ocultar el número de teléfono real de la persona que llama y hacer que parezca que están llamando desde un número diferente. Esta es una manera que los delincuentes utilizan para tratar de robar a la gente, y tratar de obtener información personal para cometer robo de identidad.

Los estafadores que llaman del número de DHS fingen ser empleados de inmigración estadounidenses. Exigen obtener o verificar información de identificación personal. A veces incluso dicen que la persona que están llamando es una víctima de robo de identidad, y que están tratando de ayudarle.

Si alguien le llama y le pide información personal o le pide de pago, CUELGUE EL TELEFONO.

La Línea Directa de DHS sirve solamente para dar información y responder a preguntas, nunca para pedirle información.

U.S. Citizenship and Information Services (USCIS) dice que cualquiera que quiera información sobre su caso o sobre su estado de inmigración puede encontrar esa información de tres maneras:

El Department of Homeland Security (DHS) también quiere que la gente ayude a rastrear a los criminales que pretenden ser funcionarios de inmigración. Ellos dicen:

“Se insta a cualquier persona que crea que puede haber sido una víctima de esta estafa telefónica de falsificación a llamar a nuestra línea directa o presentar una queja online a través de la página web de DHS OIG www.oig.dhs.gov. También puede contactar a la Federal Trade Commission para presentar una denuncia y / o denuncia de robo de identidad”.

El número del DHS OIG Hotline es 1-800-323-8603.

Suburban police work to help immigrants learn about living in Minnesota and “have them realize that they are part of our community.”

“Todd Axtell had just taken over as St. Paul police chief last summer when immigrant advocates pressed him on a longtime grievance: The department has refused to back most applications for special visas that allow crime victims who help police to stay in the country.

“The advocates wanted to know: Why can’t St. Paul’s department act more like Minneapolis police?…”