Summary of the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021

Archives

Biden Has Rescinded A Trump Order That Made Nearly Every Undocumented Immigrant A Priority For Arrest

Under Trump, the proportion of immigrants with no prior criminal convictions who were being arrested and placed into deportation proceedings shot up.

Vacuna Contra el COVID-19: Hoja Informativa

Vaccine Talking Points – Spanish / Puntos de Conversación

UPDATED 1/13/2021 – ACTUALIZADOS 13/1/2021

¿Que es la vacuna contra el COVID-19?

La vacuna del COVID-19 es una inyección que se administra para evitar que una persona se enferme con la enfermedad del COVID-19. Hasta ahora, hay dos vacunas aprobadas para uso de emergencia en los Estados Unidos: Pfizer y Moderna.

¿Cuantas vacunas se están desarrollando?

Se están desarrollando muchas vacunas COVID-19 en todo el mundo. En los Estados Unidos, cuatro vacunas se encuentran actualmente en ensayos de fase 3 a gran escala; y dos vacunas están en desarrollo temprano.

¿Cuándo estará disponible la vacuna?

Dos vacunas del COVID-19 ya están disponibles en suministro limitado y la vacunación contra COVID-19 ha comenzado en Minnesota. Estas primeras dosis se están administrando a los trabajadores de salud y a las personas que trabajan y viven en centros de cuidados de largo plazo.

¿Todos pueden vacunarse ahora?

Todavía no, pero eventualmente cualquier adulto que quiera la vacuna podrá vacunarse. A medida que Minnesota continúe recibiendo más dosis, los siguientes grupos en riesgo de exposición al COVID-19 o en riesgo de enfermedad grave por COVID-19 serán los siguientes en poder acceder la vacuna. Los grupos asesores federales brindan orientación sobre quién serán los próximos en recibir la vacuna, y un grupo asesor estatal brinda recomendaciones sobre cómo aplicar esa orientación en Minnesota. Tanto los grupos asesores federales como estatales decidirán el orden de quién será el próximo en recibir la vacuna. Gradualmente, la vacuna estará disponible para más personas. Es probable que esto no suceda hasta el verano.

¿Y los niños?

La vacuna del COVID-19 no estará disponible para niños menores de 16 años hasta que se completen más estudios.

Datos acerca de la vacuna contra el COVID-19

La vacunación contra COVID-19 lo ayudará a protegerse de enfermarse por COVID-19. Las dos vacunas COVID-19 actualmente disponibles requieren dos dosis para estar completamente protegido. Es importante que reciba la segunda dosis en el plazo correcto después de la primera dosis. El personal de salud lo ayudará a determinar cuándo debe regresar para la segunda dosis.

Las vacunas COVID-19 no pueden enfermarlo con la enfermedad COVID-19.

Las vacunas COVID-19 no producen resultados positivos en las pruebas virales para COVID-19.

Recomendamos vacunarse incluso si ya ha estado enfermo con COVID-19. La vacuna puede ayudar a prevenir enfermarse por COVID-19 otra vez.

No debería tener que pagar por la vacuna COVID-19.

Vacunarse es una de las muchas herramientas importantes para ayudar a detener esta pandemia. Aún tendrá que hacer otras cosas para prevenir la propagación del COVID-19, como usar una máscara o cubrebocas, mantenerse alejado de los demás (2 metros o seis pies), quedarse en casa si está enfermo y lavarse las manos con frecuencia.

Tiene derecho a rechazar o aceptar la vacuna del COVID-19: https://www.fda.gov/media/144625/download

¿Hay efectos secundarios después de vacunarse?

A veces. Estos efectos secundarios suelen durar uno o dos días y, por lo general, no le impiden completar sus actividades diarias. Estos síntomas son el resultado de nuestro cuerpo respondiendo a la vacuna (también es normal no tener ningún síntoma). Los efectos secundarios más comunes incluyen dolor en el brazo donde recibió la inyección. Otros síntomas incluyen dolores musculares, cansancio, dolor de cabeza y quizás fiebre (la fiebre es menos común).

¿Hay costo para vacunarse?

La vacuna COVID-19 se proporcionará a las personas sin costo. Sin embargo, los proveedores de atención médica tienen derecho a cobrar una tarifa por administrar la vacuna a alguien. Esto significa que es posible que se le solicite la información de su seguro cuando reciba la vacuna COVID-19. Aún podrá recibir la vacuna COVID-19 si no tiene seguro y / o no puede pagar la tarifa de administración.

¿Se deberá de continuar el uso de la mascarilla después de vacunarse?

Es importante que todos sigamos utilizando todas las herramientas disponibles para ayudar a detener esta pandemia a medida que aprendemos más sobre cómo funcionan las vacunas COVID-19 en condiciones de la vida real. Incluso después de haber recibido dos dosis de la vacuna, debe continuar siguiendo todas las pautas de salud pública para reducir la propagación de COVID-19. Esto incluye usar una máscara, mantenerse a 6 pies o dos metros de los demás, hacerse la prueba del COVID-19 cuando sea necesario y cumplir con los requisitos de cuarentena y aislamiento. Continúe siguiendo las instrucciones en su lugar de trabajo, escuela y otros entornos también.

Para más información

Hay mucha información incorrecta circulando por las redes sociales. Para más información consulte:

https://espanol.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/8-things.html

https://espanol.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/faq.html

https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/materials/spanish.html

US judge blocks Trump administration’s sweeping asylum rules

Judge Donato halted regulations that would eviscerate asylum, making it almost impossible for victims of persecution to find safety in the United States.

‘I can’t believe this is happening to our country’: Minnesota immigrants watch with alarm as Trump insurrectionists attack U.S. Capitol

How COVID-19 Vaccines Are Made

12/21/2020

The first COVID-19 vaccines have come out within a year of the COVID-19 virus being discovered. There are many questions about how a vaccine could be created so quickly. With help from the federal government, the process was able to happen faster and more efficiently. It is important to know that steps to check for safety were not skipped. These timelines show how the process to make COVID-19 vaccines was made more efficient compared to how other vaccines are made.

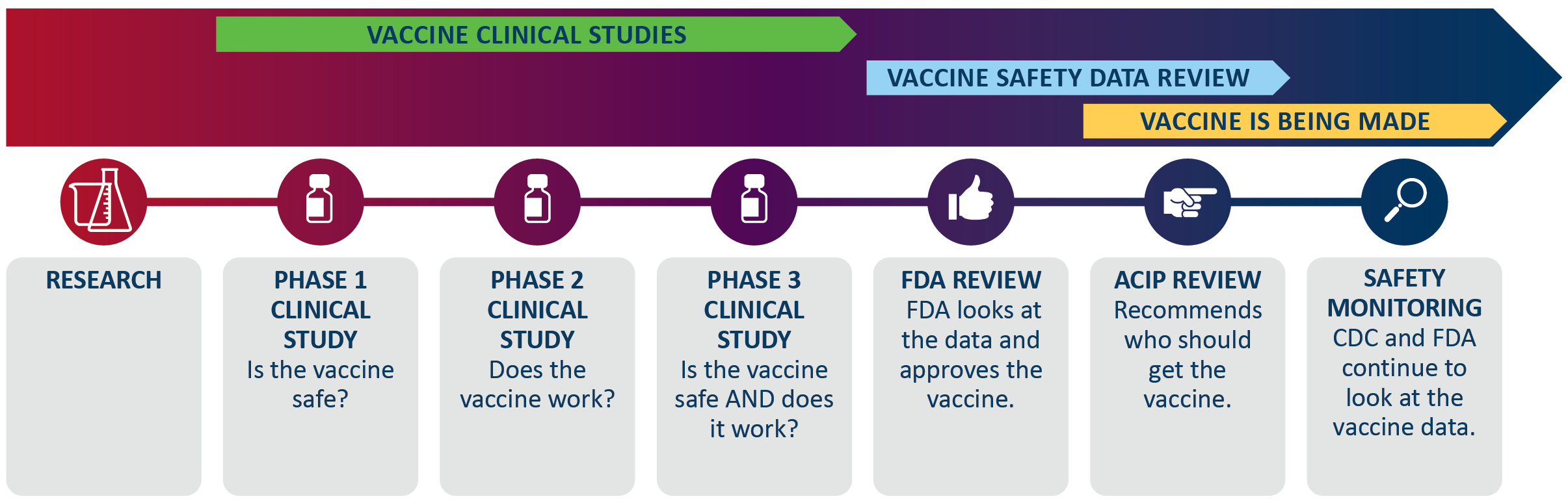

How vaccines are made

The process to make a vaccine can take up to 10 years.

- After research is done, a vaccine goes through three human clinical studies; each one has more and more people.

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves the vaccine after their science advisory group reviews the study results.

- Then a national advisory group, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), recommends who should get the vaccine.

- After that, the manufacturer starts to make vaccine.

- As people get the vaccine, CDC and FDA continue to look at the safety data for the vaccine.

A vaccine process starting with research. Then vaccine clinical studies. Phase 1 clinical studies happen first where they find if the vaccine is safe. Then phase 2 clinical studies where they find if the vaccine works. And then phase 3 clinical studies where they find if the vaccine is safe and if it works. Next, the vaccine safety data review. The FDA review is when FDA looks at the data and approves the vaccine. Then the ACIP review to recommend who should get the vaccine. Safety monitoring is last, where CDC and FDA continue to look at the vaccine data. Vaccine starts being made after the FDA review and continues past safety monitoring.

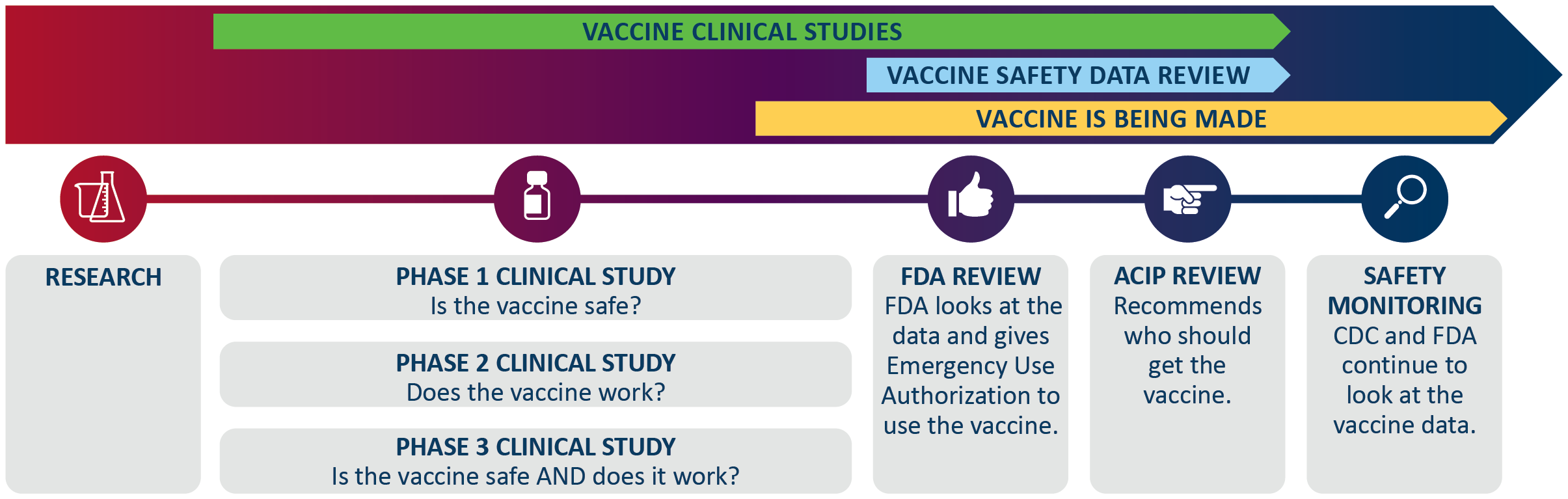

How COVID-19 vaccine is being made

- Earlier research on the coronavirus and advances in vaccine technology gave this process a jump start.

- Sometimes finding money for the vaccine studies can take a lot of time, but for COVID-19 vaccine, the federal government provided a lot of money.

- Manufacturers recruited participants for all three phases of the clinical studies at the same time, instead of waiting for each one to be done.

- Manufacturers are also making vaccine while the clinical studies happen.

- Approving a vaccine with an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) also takes less time. Getting a safe vaccine that works is the number one priority.

- Groups at the federal level are not letting anything delay them from reviewing and hopefully approving vaccines. For example, the FDA added a lot of staff to shorten the review process from months to weeks.

- The vaccine will only receive approval if the studies show that the vaccine is safe and works.

A vaccine process starting with research. Then vaccine clinical studies. All three phases are happening at the same time. Phase 1 clinical studies happen first where they find if the vaccine is safe. Then phase 2 clinical studies where they find if the vaccine works. And then phase 3 clinical studies where they find if the vaccine is safe and if it works. The vaccine clinical studies go until the end of the ACIP review. Vaccine starts being made near the end of the phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical studies and extends past safety and monitoring. Next, the vaccine safety data review. The FDA review is when FDA looks at the data and gives emergency use authorization to use the vaccine. Then the ACIP review to recommend who should get the vaccine. Safety monitoring is last, where CDC and FDA continue to look at the vaccine data.

There are still things that we need to learn about the COVID-19 vaccine, such as how long protection from the vaccine lasts and how well it will work in the general population, but these are not reasons to delay getting a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine out to people.

For more information, see COVID-19 Vaccine (www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/vaccine.html).

Minnesota Department of Health | health.mn.gov | 651-201-5000

625 Robert Street North PO Box 64975, St. Paul, MN 55164-0975

Contact health.communications@state.mn.us to request an alternate format.

A Traditional Karen Dress, a Pair of High heels, a Pandemic, and an Office Telephone Tree: Shall Ber’s Last Ordeal on the Road to Citizenship

“I was not worried, because deep in my heart I knew I would become a U.S. citizen on that day.”

Backstory: “You couldn’t go anywhere”

On an April day in 2009, an airliner carrying 18-year-old Shall Ber and her older sister, Sine Nay Win, touched down at an east coast airport. The city was either Washington, D.C. or New York; Shall says she was too exhausted to pay attention. The two young women had never before traveled beyond their home in the rugged country along the Burma-Thailand border. Now they were half-way around the world. They had left the Bangkok airport days earlier, had taken several shorter flights with long waits in airports, and now at last they were entering the United States as refugees.

For as long as Shall could remember, she had lived in a Thai refugee camp. Before that, her Karen family had been farmers in the jungles of southeast Burma, where the Karen people had lived for centuries. But Shall’s family had been driven from that area by civil war and by the Burmese soldiers who raided Karen villages. Burma’s military government wanted the Karen people out of the country. When the attacks became too vicious and frequent, Shall’s father, a widower, had fled across the border into Thailand with his son and three young daughters. There, with the support of the Thai government, refugee camps had been established by the United Nations and other international organizations to accommodate ethnic minorities driven out of Burma.

Officially, the camps were not prisons, but refugees were not given official papers to travel outside. “All you could do after school is you go home, you sleep, you wake up, and you go to school,” Shall recalls “You can’t go anywhere. You want to go to the city, but you can’t go outside the camp because you don’t know people who know how to drive, so I just stay in the camp and study, study, study.” For entertainment, there was a movie theater in the camp; “like a big TV in a bamboo shed,” Shall says, “with tables and chairs to sit. You had to pay, but you could watch movies and programs with your friends.” She says the best part of growing up in camp was “to study and visit people and have friends like kids like to have friends.” The worst problem back then was that “you couldn’t go anywhere.”

The camps were intended as temporary shelters for refugees awaiting resettlement someplace else, but due to politics or global crises, many people lived in the camp for years or even decades before it was possible to leave. Many still remain today.

Refugees in Shall’s camp received basic food and clothing from the United Nations and other organizations, but there were still unmet needs. The rice and fish paste provided in camp were good, but they were even better when supplemented with other foods. Like many men, Shall’s father kept a small garden, where he grew bananas and papaya as he had done in Burma, but that was still not enough.

The small economy in camp provided little employment, so men like her father would sometimes sneak away to cut bamboo for landowners in the jungle or to work on Thai fishing boats. They would return after a few weeks with a little cash and some choice items of food and clothing for their families. Shall’s oldest sister, who knew people who knew how to drive, would sometimes go to Bangkok, where she would buy cool or useful items at the open-air markets and bring them back to sell in a little shop she ran in the camp. These unauthorized trips were a way of making camp life better for the family—and also of dealing with confinement.

When their plane landed in the United States, Shall remembers that a Karen representative from their sponsorship organization met them at the airport. Exhausted by days of travel, she and Sine wanted only to sleep. After Thailand’s steamy tropical heat, April on the East Coast felt frigid. Even in their exhaustion, Shall and her sister were grateful when they were taken to pick up warm clothes, some groceries, and a few housewares from their sponsoring organization.

Soon afterwards, the organization helped Shall and Sine reach Syracuse, NY, where a community of Karen refugees was already established. The sisters were shown to a small, one-bedroom apartment they would share while being introduced to life in the United States.

Shall says the apartment was an instant delight for several reasons. First, unlike the rustic, communal facilities in Tham Hin camp, the apartment had a full American-style bathroom. She remembered being on the airplane and needing a restroom. The restrooms had been explained before boarding, but she was shy to think that people would watch her walking down the long aisle towards the green light, and she wasn’t sure she would know how to use the equipment once she got there. So she waited—and waited some more, and then more still. It was very uncomfortable, she says.

Finally, she made the long walk and found her way into the tiny room. Afterwards, the door she had found partly open on the way in did not seem to open to let her out. There seemed to be no knob or handle or place to push. Feeling both silly and anxious, she fumbled with it for a long time and then began knocking. Finally, she says, someone opened the door from the outside, as she had done on her way in. With that memory not far behind her, Shall gazed with appreciation at the Syracuse apartment’s spacious bathroom with the door that opened and closed so easily. “I was very young at 18,” Shall says now.

Another delight in the apartment was that each person had her own soft bed. “In the camp,” she says, “you had to sleep on the bamboo.” Living quarters were small, crowded, and built only a few feet apart, often with thin walls of vertical bamboo sticks, and with more bamboo sticks stretched horizontally across a frame inside to make a bed for several family members. To “sleep on the bamboo” with others was not a terrible hardship, Shall says, but it was not really comfortable “unless you were very tired.” To Shall and Sine, finally at the end of their long journey, it felt strange and luxurious to sink into soft, individual beds in the privacy of an apartment for only two people.

In Syracuse, the sisters eventually became more accustomed to life In the United States. One of the biggest challenges to new refugees, especially adults, is the language barrier. Not speaking the local language can cause isolation, low self-esteem, and even depression, as well as creating practical problems in everyday life. Like other new arrivals, Shall and her sister took courses in English as a second language. With help from the Karen Organization in Syracuse, they applied for green cards and prepared to enter the labor force.

While visiting in a neighbor’s apartment, Shall met another guest who soon became her husband, a Karen refugee named Aung who had been in Syracuse just a bit longer than Shall. At that first meeting, Shall thought Aung was “quiet and mature, but he had a lot of energy. He seemed like a good person. He loved God—and he was good at cleaning.” What did Aung think of her? “Oh, he never says anything, but he was in love.” A year later, the two had married and were starting a family.

While Shall and Aung were adjusting to life in Syracuse, her father, brother, and oldest sister had resettled as refugees in Albert Lea, Minnesota. Sine soon left Syracuse to join them. In 2017, Shall’s new family, now with two young children and expecting a third, followed along, joining the rest of the family in Albert Lea, where job prospects for Aung were better. Also, Shall says, the Syracuse public school system would not allow her two children to attend the same school. Officials thought the kids would enculturate better if kept apart. Shall’s sister in Minnesota said that would not be an issue in Albert Lea, so after eight years Shall’s full family was finally reunited there.

Prelude: “The 100 Questions”

By fall of 2019, Shall’s husband held a good job at a pork processing facility in Austin. They had three children and a nice apartment near their two oldest children’s school. Their youngest was a toddler and Shall was expecting her fourth child. Born in the United States, the children were all U.S. citizens. In November, Shall and Aung decided to fill out N-400 forms, beginning the process of becoming naturalized citizens themselves.

Naturalization is a complicated, multi-step process that requires completing forms and presenting official documents to confirm one’s identity as a lawfully present and law-abiding U.S. resident for a required length of time. The process includes a test of English language proficiency and a “citizenship” exam about details of U.S. history and government. The final step is a brief courtroom oath-taking ceremony in which the applicant renounces citizenship in any other nation and asserts sole allegiance to the United States.

Shall and her husband were going through the process because they wanted to be recognized as full Americans, not just “resident aliens,” not just people who don’t “really” belong where they happen to live. Shall and Aung had never officially belonged anywhere, neither in Burma nor Thailand, nor anywhere else. In the United States, they had seen people voting, which seemed like a mark of official recognition as well as a right and privilege of belonging. They hoped someday to be able to vote and to travel internationally on a U.S. passport. They wanted a more secure claim on the American freedoms they had learned about in orientation sessions. “We wanted to live freely and vote,” Shall says.

The naturalization process can move more or less quickly for different applicants. It requires applicants to provide or fill out many documents from various divisions of government. There can be long waits while documents from one step are processed before the next step begins. Would-be applicants are often daunted by the complexity of it all, especially by the exams.

In November, 2019, when Shall was six months pregnant, she and her husband began the citizenship process together. Shall says it was confusing at first, but they were lucky to find an able helper in Maylary Apolo, a case handler at the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota’s Austin office. Maylary answered questions about what forms were required, how to fill them out, and where to send them. She knew which supporting documents were needed and how to get them, and she provided advice and encouragement.

The couple submitted their N-400 forms at the same time, and in a few weeks received notice of a “biometrics” appointment, where their fingerprints and other identifying data would be recorded. They attended together, almost like a couple on a date: “Together, together,” Shall says, “Always we start everything together.” The next step was to wait while their applications were checked; then there would be a personal interview that included the English proficiency test and the citizenship exam.

While they were waiting, their fourth child was born in late February. This was a change in family they would need to note on their citizenship applications. Shall dutifully called Maylary at ILCM and was surprised when Maylary said she had just heard that Shall’s big citizenship interview was scheduled in Minneapolis within about two weeks.

Shall was alarmed. She wanted to be ready for the exams. She had been preparing off and on as time permitted, but she still needed to polish her English. And she thought about the citizenship test, with its “100 questions that you had to know and remember because you don’t know which ones they will ask.”

Then she thought of her four young children, of the care and housework a family of six requires, of the daycare she provided for her sister’s four children while the sister worked, and “of all the things there are to do with a new baby in my arms.” She told Maylary, “I don’t think I can do this interview.” And Maylary replied, “I think you can.”

Shall at least knew she wanted to. With an infant in arms, she enlisted her 10-year-old daughter, Lily, as an English tutor, especially for pronunciation. Lily would say a word for her mom to repeat and was not always pleased with what she heard, Shall reports. Often Lily would hear Shall’s repetition, frown, and then say, “No, Mommy, it’s not like that. You have to make a sound like this . . .” and then demonstrate. This helped a lot, but there were also the 100 citizenship questions. Shall read over the questions and brief answers most nights before she fell asleep, but she wasn’t sure she would remember them all.

As the interview drew near, Maylary called and invited Shall to her office to practice the tests:

“So I go there, and she asks me the 100 questions, and — oh my god! — I know more of them, but some made me confused, so I don’t get it. And then she wanted me to do the writing test, but I told her I’m not good at writing. I said, ‘You talk, I understand; I talk, you understand— Okay! But I’m not good at writing.’ Then Maylary told me, ‘Try!’”

“She called off the state California, and I don’t know how to write that. Then she called the state Dela? . . . Dela? . . ., and I don’t know how to write that. She called more states, and then she said ‘You did okay with your 100 questions; you just have to look at them some more, but you have to focus on writing. Your speaking is already good, but your writing is low, so try to do better.’ So I go home and I try, I try, I try.” Shall asked Lily to say the state names and other words while Shall practiced until she could write them correctly.

On the day of the interview, Shall’s whole family plus her good friend Emily traveled with her to the courthouse in Minneapolis. An ILCM probono attorney, Thomas Lovett from Ballard Spahr, joined them, and the group sat together in a waiting room until Shall was called.

Shall says she was not nervous while waiting. “I felt relaxed with my husband and kids with me. I thought, pass or not pass — it doesn’t matter. I am happy with my family.” When Shall’s turn came, she and Thomas entered and sat together. The family waited in the lobby. In the interview room, Thomas confirmed the new baby and some details of Shall’s situation.

Then the interviewer questioned Shall briefly about her situation, and moved into asking some of the “100 questions,” occasionally jotting notes or marking documents during Shall’s answers. Finally, she asked Shall to write something about Christopher Columbus. After reading Shall’s answer, the interviewer began sorting through the papers on her desk. Then, she pushed some documents over for Shall to sign: “I signed everything and then I asked her: ‘I passed?’” “Yes!” came the cheery response, “You passed.” Shall says, “and then I’m so happy!”

Returning to the lobby, Shall says, “I was going to pretend to my family that – ‘Aww, I didn’t pass,’ but my husband already saw me and was like, ‘She’s good. She passed.’ I was laughing, Emily was happy, and my husband was smiling. They were all so happy!” Before driving back to Albert Lea, the whole group celebrated with a feast at a downtown Chinese restaurant: “You had to celebrate, because it was a big day!”

The Last Ordeal:

A few months later, an official-looking envelope arrived in Shall’s mailbox. Inside was a letter from U.S. Customs and Immigration Service that began by thanking Shall for her interest in becoming a U.S. citizen. It said that to complete the process she “must now appear at a Naturalization Oath Ceremony” scheduled at the Minneapolis federal courthouse at noon on June 23, 2020. By now the Covid virus was circulating everywhere, so instead of the usual courtroom venue, the event was scheduled outside in Courthouse Plaza to reduce chances of spreading the virus.

Maylary contacted Shall to be sure she was prepared for the event, which was the last step in the naturalization process. After every step before, Shall had posted a photo and report on her Facebook page, and her family and friends had replied with congratulations, encouragement, and exclamation marks. The whole family had attended her citizenship interview in March. Everyone was rooting for Shall, remembering her interview, and awaiting a celebratory conclusion.

But now, Shall and her husband were worried about the virus and about drawing the family to a crowded city where they might become infected. Also, the day was going to be unusually hot, not good for babies or older people. They decided that Aung would stay with the family while Shall’s friend Emily drove her to Minneapolis for the event. They would all keep in touch by phone.

Anticipating this day, Shall had long ago ordered a traditional Karen dress from a Karen seamstress in Thailand. Now she donned the dress and selected a pair of “cute little heels” for the special event. To aid navigation, Emily asked Shall to photograph the Courthouse Plaza’s address printed in the U.S.C.I.S. notification letter.

With that info secured, the two headed north on the highway, talking about everything like two good friends on a road trip. Much later, while “Emily was talking a lot about the kids she loved,” Shall noticed a large green sign zip past the moving car’s window. Something seemed wrong. It slowly dawned on her that the sign had said “Rochester.” They had somehow taken a wrong turn farther back.

Emily was heading for the correct street address, Shall said, “but she thought it was in Rochester, so this was a delicate situation.” Shall thought now they might not arrive in time, but she did not want to make Emily feel bad by saying they had gone the wrong way. “I said, ‘Um, Emily, this is Rochester, not Minneapolis,’ and I showed her on the Google map where the Courthouse Plaza was and where we were.” They turned around and started towards Minneapolis.

On the way, Emily worried they would be late and miss the ceremony. “She wanted me to call the court house and tell them,” Shall says, “so I called the number and had to wait” because only a few courthouse staff were working due to Covid-19. “Then someone came on talking and said I would have to wait for another person, so I waited more with the music.” Meanwhile, Emily drove and fretted about being late. “Finally,” Shall reports, “a voice on the phone was talking, and then it said ‘Your expected wait time will be 999 minutes.’

“I didn’t think we could wait that long,” Shall says, “but I wasn’t worried because deep in my heart I knew I would become an American citizen on that day.”

In Minneapolis, the problem was where to park. “That town has lots of people, lots of buildings, and you don’t know where you have to go,” Shall says, but Emily had ideas, and they found an underground parking ramp close to the courthouse. Next was a walk up many stairs and then some quick striding along the sidewalk. Time was getting short. Emily had asked people for directions and knew the way, but Shall began lagging behind. The day was hot, and the shoes were hurting her feet. Emily urged her to take them off, so she could walk faster, but Shall refused: “It would not look cute and beautiful, and people would look at me weird walking here with bare feet.” Emily slowed her walk so Shall could keep up.

They arrived at the plaza to find the event’s staff friendly and reassuring. There was plenty of time. About 50 people were already waiting to take the oath. Shall just needed to find her place in a socially-distanced group and wait with them in one part of the plaza. There, city and immigration officials congratulated the group and spoke to them about citizenship. Around the edges of the plaza, a small scattering of friends or relatives stood watching the proceedings.

Shall stood on her marked spot while the tall courthouse loomed over everyone and the hot sun beat down. She felt excited and grateful to be so near becoming a U.S. citizen, yet her feet hurt and she also thought, “It’s so hot! Why this year? Why now? Why so hot? Usually people go inside, sit down, have nice air conditioning, but here it’s under the sun, cover your face, wear a mask – oh, my god!” Still, she was happy. When her group was called, she stepped into the area before a court official, completed the oath, and then waited until a staff member walked around the socially-distanced group handing each new citizen their official certificate and a miniature U.S. flag.

After the ceremony, Shall stood in her Karen dress and little heels on the sunbaked plaza, holding her certificate and her little flag while the big courthouse flag on the pole behind her barely stirred in the hot sun. Emily took some photos with her phone and then called for a table at a nearby Chinese buffet. They thought they should have something to eat before the long drive home.

While they were in the restaurant, Shall “was missing my husband, missing my kids.” So she returned to the buffet line and filled some takeout boxes for Aung and the children before she paid the tab and began the trip home.

Walking to the parking ramp, Shall mentioned again that her feet hurt “and Emily was like, ‘Shall, do you want to take off your heels now?’ and I’m like, ‘Yes I want to take them off.’ I don’t care if it’s not cute anymore. My feet hurt, so I just take them off and hold them in my hand. And I don’t even care if people look at me weird.”

When they arrived back in Albert Lea, the whole family ran out to greet Shall with cheers and congratulations. People were dressed up, and “the kids were like, ‘Yay, Mommy, you’re home now! We’re so proud of you – you’re a citizen now!’ And they were so happy that I brought them nice food.” Aung, who still hadn’t been called for his big citizenship interview, stood beside his wife, looking silently proud of her. Friends and relatives were circulating, and everyone was eating while people took a lot of pictures to mark the occasion.

One of the photos shows Shall, Aung, and their four children standing rather formally in their living room. Shall now holds her new baby along with her citizenship certificate and flag, and she still wears her Karen dress. Aung has changed into a traditional Karen man’s outfit. The oath Shall had taken that day requires people to renounce citizenship in any other nation and assert sole allegiance to the United States. That was not a problem for Shall. The Karen have an ancient ethnicity of their own, but not a nation. They had been driven from Burma and sheltered in Thailand, but they have not had guaranteed citizenship in any country during Shall’s lifetime. Shall says the photo with her traditional dress, small flag, and certificate “shows I am Karen and I came to the United States and now I am a citizen.”

So, after much hard work and persistence, and with help from the Thai government, the United Nations, many foundations and NGOs, an Obama-era refugee program in the United States, the Immigrant Law Center of Minnesota, and friends, family, and Karen organizations already in the United States, Shall went somewhere after all. Her journey to citizenship began in the jungles of Burma when she was too young to remember and ended fittingly almost 30 years later on the Minnesota prairie with a classic American road trip and then a return to home, family, and belonging.

Postscript:

Asked what she would say, now, to someone who does not like immigrants coming to the United States, Shall said she might say, “I was an immigrant. Now I am an American citizen, just like you. You can talk to me in English. And I can talk to you.”

—–

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) Extended!

On December 9, the Trump administration obeyed a court order and extended Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for nationals of El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nepal, Nicaragua, and Sudan through October 4, 2021. This status had been set to expire on January 4, 2021, leaving hundreds of thousands of TPS holders vulnerable to deportation. With their status extended through October 4, 2021, the incoming Biden administration will have time to fulfill its promises to protect these long-term residents of the United States.

The extension of TPS applies only to people who already have that status. It does not open the door for any new applications. The presidents of Guatemala and Honduras have asked that nationals of their countries who do not currently have TPS be allowed to apply for this status, based on the damage done to their countries by Hurricane Eta and Hurricane Iota. The Trump administration has not responded to their requests. President-elect Joe Biden has already committed to designating Venezuela for TPS after he takes office.

TPS holders from these six countries who need to renew their drivers’ licenses or show employers that they are still eligible to continue working may do so. Employment Authorization Documents (EAD) are automatically extended. For proof, TPS holders download a copy of the Federal Register notice, which is attached to this article as a PDF.

In addition to these six countries, four other countries still have TPS designations:

- South Sudan—continuing through 5/2/2022

- Somalia— continuing through 9/17/2021

- Syria— continuing through 3/31/2021

- Yemen— continuing through 9/3/2021

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is an immigration status which provides recipients with an 18-month authorization to live in the United States and also offers a work permit for people from designated foreign countries that have been impacted by a natural disaster, armed conflict, or other extraordinary circumstances. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has the sole authority to designate and then renew or re-designate a country for TPS.

TPS is a temporary status, granted because conditions in the home country prevent safe return of that country’s nationals living in the United States, or because the home country temporarily is unable to accept their return. For some of the designated countries, TPS has been extended year after year when country conditions have not improved, so that many TPS holders have lived in the United States for decades, with strong ties to work, families, and communities.

12092020 TPS extensionVaccine Planning and Distribution Key Messages: MDH

Updated 12.08.2020

High level key messages

- There are three principles that will guide our distribution of the vaccine.

- Immunize for impact, and maximizing immediate health benefit, reduce death and serious illness, and minimize the harm created by COVID-19

- Equitable distribution and access, making sure no procedural or structural issues impact access to the vaccine among any particular group or population. And we want Minnesotans in every corner and every community to know they can trust the process, the safety, and the effectiveness of the vaccine.

- Transparency and sharing information as quickly as possible with Minnesotans.

- Minnesotans can be confident that the infrastructure in Minnesota is in place to deliver a COVID-19 vaccine quickly, equitably, and safely to Minnesotans in every corner the state.

How the priority groups were selected

- We know that especially in the earliest weeks of vaccine distribution there will not be nearly enough vaccine to meet demand for the groups identified as top priorities in Phase 1a, not to mention the many other groups that we know have legitimate arguments for deserving early vaccines.

- The National Academies of Science released a report on framework for equitable allocation of COVID-19 vaccine. With that guidance in mind, the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice (ACIP) made recommendations for priority groups who should receive early limited doses.

- For phase 1a, the first phase, they said health care personnel and long-term care residents should be included.

- MDH will follow ACIP guidance, and we worked with our MN Vaccine Allocation Advisory Workgroup to take ACIP guidance and apply it to MN.

- Their guidance reflects an emphasis on using the early, small amounts of vaccine to make the maximum possible impact (“Immunize for Impact”) on protecting our most vulnerable and exposed – including health care workers and long-term care residents.

- We prioritized the first group for Minnesota even more by reviewing the risk criteria presented in that national Framework for Ethical Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine, published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. The risk criteria considered were:

- Risk of infection: Individuals have higher prioritization because they work or live in settings with a higher risk of disease transmission occurring because COVID-19 is circulating.

- Risk of severe morbidity and mortality: Individuals who are older and that have comorbid conditions are at higher risk of severe outcomes and death.

- Risk of transmitting to others (at work and at home): Individuals have higher priority because the live or work in settings where transmission is more likely to occur.

- Risk of negative societal impact: Individuals have higher priority due to the extent which society and other people’s lives depend on them being healthy.

- As you can see, it’s not just the risk to the individual, it’s also about risk to very vulnerable groups that a person serves that gets taken into account.

- Minnesota has identified three sub-priority groups. We have guidance posted on our website with more details (will be posted at 1:30 p.m.): COVID-19 Vaccine Information for Health Professionals (https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/vaccine/index.html).

How vaccine will be distributed

- Initial vaccines will be given in closed settings – we’re bringing the vaccine to the priority groups. There is not a “list” that Minnesotans need to get on to get vaccine. Since phase 1a is based on employment and place of residence, people eligible for this category will be contacted by their employer or the facility where they live, or possibly local public health, to let them know when vaccine is available to them.

- Vaccine will go directly to providers who are enrolled with us to give COVID-19 vaccine.

Find more information on COVID-19 vaccines at COVID-19 Vaccine Information for Health Professionals (https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/vaccine/index.html)