News > Immigration In Minnesota

“I wanted to serve the country”

Posted on Feb 12 2018

“In high school, I always saw the recruiters come into our school. I was always excited about joining, about serving.”

Back then, Samuel* couldn’t enlist. He felt that the United States was his country. He had lived here since he was nine years old. But he had no legal status. He didn’t even have a work permit.

“There was no way I could even approach them without telling my story,” he recalls, “and I was afraid of being turned in [to immigration authorities.]”

Then came DACA—Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals—in 2012. Samuel filled out the forms, paid the $495 fee, waited, and finally got his DACA status and work permit and social security number.

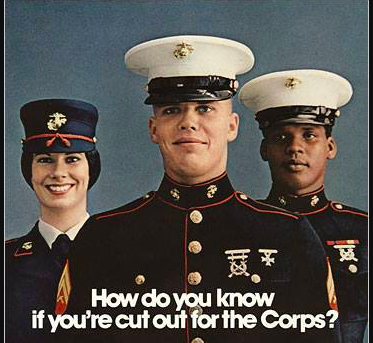

He headed for the U.S. Marines recruitment office.

“I wanted to join the military,” he says. “I wanted to serve the country, to prove I was loyal to the country, that I didn’t have no other home but this home that I knew.”

The recruiters processed his paperwork, his social security number. Then they hit a snag. The paperwork came back—declined because of a limit on his social security number, they told him. There was a limitation noted, one that said “work authorization only.”

Sorry. No enlistment. Not until you can get that off your social security number.

So now Samuel waits again. He graduated from high school, has a responsible job and his own home. But he can’t enlist in the military to prove his loyalty to the country he knows as home.

One of his brothers is a U.S. citizen. That brother “put in a request for us to have a brother-to-brother case, legal status.”

The family reunification visa that Samuel is waiting for is part of the program Trump vilifies as “chain migration,” saying it gives immigrants an easy way to bring in distant relatives.

Samuel thinks of the visa as brother-to-brother, which doesn’t feel like a distant relative at all. His visa process is not easy or quick.

“The waiting period is ridiculous,” Samuel says. “They’re working on cases back in 1999 now. So I still got five more years to go.” Samuel thinks the program should be reformed, so that people do not have to wait 20 or 25 years to get a visa.

* We have changed Samuel’s name in this story. As a matter of policy, we usually change the names of immigrants when telling their stories. While the stories are real, and while the individuals have agreed to let us use their stories, we choose to protect their privacy by not using their real names.